Soul Of A Nation, Heart of A Community

“No other field is closed to those who are not white and male as is the visual arts. After I decided to be an artist, the first thing I had to believe was that I, a black woman, could penetrate the art scene, and that, further, I could do so without sacrificing one iota of my blackness or my femaleness or my humanity” – Elizabeth Catlett

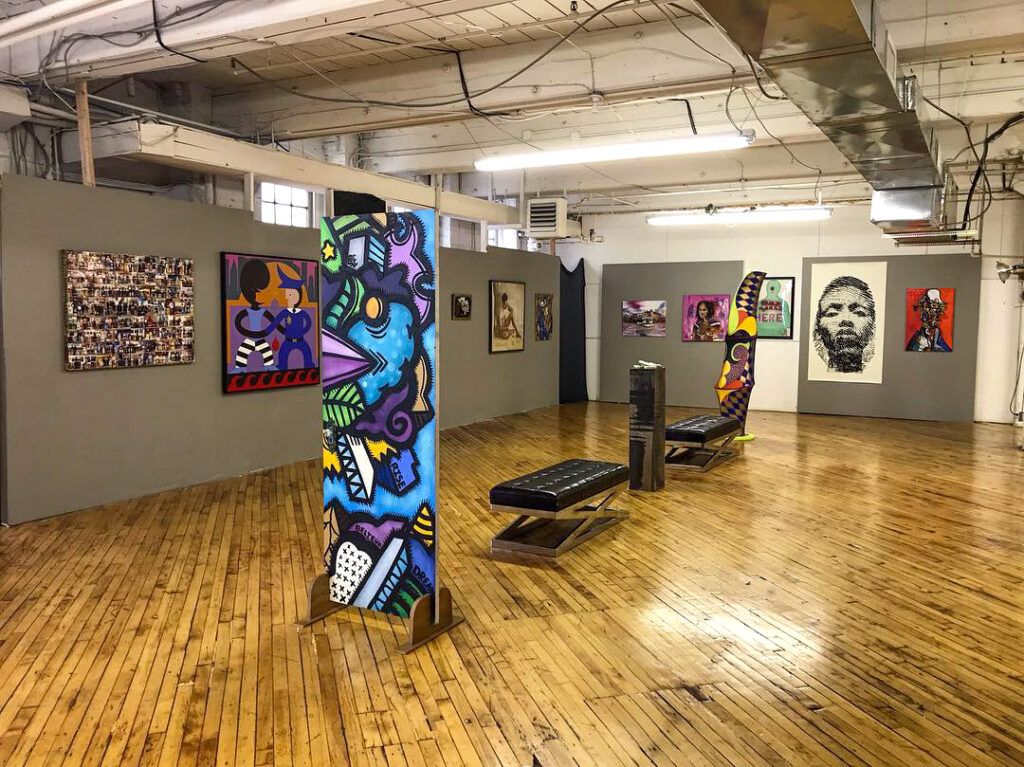

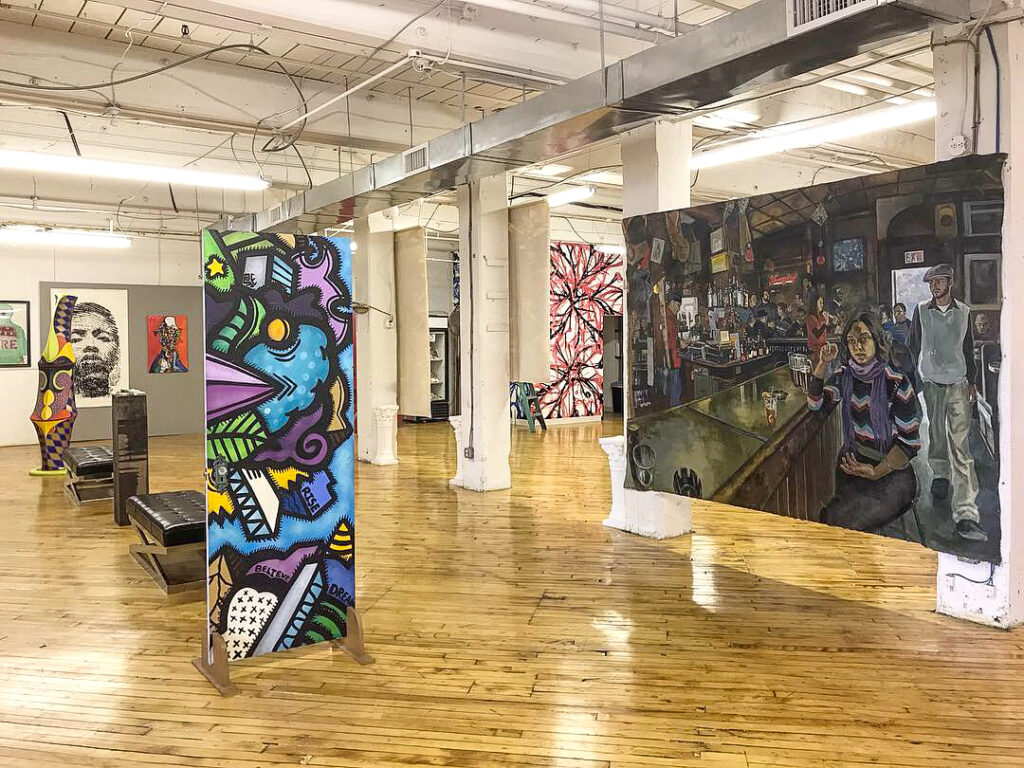

With the rise of attention in works by women, artists of color, and the LGBT community, museums have seemed to pivot in a new direction – prioritizing inclusiveness – in an attempt to “correct” the underrepresentation of such artists in its programming. “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983” featuring the artwork of pioneering black artists, poets, and photographers opened at The Broad Museum in Los Angeles on March 23rd, 2019. This is the exhibition’s third stop in the United States and first on the West Coast – after originating at the Tate Modern in London in 2017. The exhibition celebrates the artists and the movements they helped to institute in the two decades after 1963 when the Civil Rights movement started to gain steam.

Reminiscing through photos from my visit to its installation at the Tate Modern, I attempted to re-familiarize myself with the retrospective by trekking back through the works, re-living some of the feelings I had at first sight. As I browsed through the display, I pondered how the exhibition would be received by the city and its artistic community. How would the museum curators arrange its display inside the institution? The Broad Museum’s plush galleries and modern architectural design have a way of rejuvenating the excitement of the artwork on view. It has the uncanny ability to reintroduce work to its contemporary audiences with newness as if these works were just acquired from the artists’ studios moments before they furnished the walls. I was excited to see if this magic would lend itself to the newest exposition, allowing the artists themselves to relive the moments and actions that spawned these objects. But what in the exhibition would be “adjusted” before it made its Tinseltown debut?

It’s always thought-provoking to see what works are chosen for display and why. Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum, 1992, at the Maryland Historical Society, brought awareness to institutional collecting and exhibiting practices that often favored the display of works by white men. Through this installation, Wilson was able to unearth works from the collection – alluding to the biases that these spaces have – presenting a case study impossible to ignore. With this in mind, I asked myself if The Broad Museum and its curatorial team would try to lean toward the promotion of more commercial works from the artists – minimizing the history of the period – to focus on drawing more attendance for local and national visitors. Speaking to The Art Newspaper, Founding Director of The Broad Joanne Heyler spoke to the process of deciding on whether to take on this exhibition and how it almost didn’t happen. “There is not an overlap between the artists in the show and the Broad’s collection,” Heyler remarked. With many of the featured artists spending a significant part of their careers in the city and surrounding areas (Betye Saar and Noah Purifoy among the most notable), the biggest question I had for the Broad acquisitions team is – Why not?

Greeting you at the entryway is Carousel Change, 1970 by Sam Gilliam, a large piece of canvas resembling bed sheets with different shades and splatters, which I can imagine lived on the floor of Gilliam’s studio initially. The way this work was displayed at the entrance made me feel a bit uneasy. The last time I saw this work at the Tate, it was presented – in what seemed to be its entirety – full and stretched across the wall accentuating its scale and the vibrancy of color it contained. It welcomed the viewer like a big hug from a grandmother. In this display it confronts me in the form of a mob of seven Ku Klux Klansmen dressed in colorful robes, immediately bringing up thoughts of the 2015 “Birth of a Nation” project by the artist Paul Rucker. I wonder if anyone else felt this way? I digress.

Accompanied by a soundtrack curated by Quincy Jones – which is available via QR code visibly accessible on the gallery walls – you’re audibly guided through the retrospective with a playlist of horn-inspired rhythms and dialogue, allowing you to experience the music that defined the time. Quincy Jones in his summary on creating the list quotes that “You gotta know where you’re coming from to get where you’re going,“ as a precursor to this curation. With hits like “Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud“ by James Brown and “Young, Gifted and Black” by Nina Simone, I was interested in experiencing firsthand how the list would correlate to what visitors experienced. So I pressed play and started to head on in. Ironically, Gil Scott Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” was the opening song.

We are introduced first to the SPIRAL Group, a collection of artists whose work reacted to the Civil Rights Movement, questioning how – as artists – they could interpret the times. Executing works in black and white only, artists like Norman Lewis, Emma Amos, Hale Woodruff, and Romare Bearden among others, sought to challenge the question of the Negro image in visual art. Lasting a few years (1963-1965), the group mounted the only exhibition titled “First Group Showing: Works in Black and White” as a response to black artists being overlooked by the institutions. Similar to a recent epidemic in major cities across the country, rising rents in the area where they gathered cost them their meeting space which ultimately led the group to go their separate ways.

You come across powerful works such as Freedom Now, 1963 by Reginald Gammon referencing The March on Washington. Depicting a scene of activists in bunches – seemingly about to march right out of the painting into the gallery – it struck me how using only the two primary colors the artist was able to conceal the races of the subjects. This manipulated viewpoint gives evidence to the “We are all in this together” motto that is often brought up during points of civil unrest in America.

The most astounding and polarizing work to me in the SPIRAL gallery was America the Beautiful, 1960 by Norman Lewis. This abstract work at first glance appears as random swipes of white house paint on a black panel, insinuating at a figure to be revealed once the viewer steps back to catch a full view. Upon further investigation, you see the shapes in the paint start to materialize and then realize you’re looking at a representation of a Ku-Klux-Klan meeting. I love the correlation in these works together. These works represent groups of people acting out its form of support for their message, which mirrored the inception of the SPIRAL group. It also puts on full display the duality of the American reality where dueling classes continue to battle for their rightful place in society. I often see the SPIRAL Group reemerging in the work of contemporary artists like using the same color palette to deliver his vision.

As the decade progressed and the voice of “Black Power” started to define itself through defiant imagery, black artists aimed at creating an identity of activism through their work. Symbols like the raised fist – The Black Power salute – and the American Flag were used as catalysts, sparking debate about the country’s treatment of its African-American citizens. This led to the emergence of the Black Arts Movement (BAM) which like the SPIRAL Group, organized their communication through artistic practices – albeit more politically charged. The gallery presents some of the imagery in the form of newsletters, caricatures, posters, and magazines in a vitrine showcasing the outreach of the groups in different forms of media.

Immediately upon entering the gallery, you can feel the tension in the work. Hinting at the catalysts previously mentioned, works like Kay Brown’s The Devil and His Game, 1970, depicting then-President Richard Nixon playing what appears to be a game of checkers with Rev Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, using black children as the game pieces. And Dana C. Chandler’s Fred Hampton’s Door #2, 1975, a sculptural replica of the front door of Black Panther Fred Hampton that was shot through by Chicago Police – eventually entering and murdering him and another Panther member. They combined a grim history within its presentation. Mixed in with these works is Blackboard, 1967-71 by Cliff Joseph, showing a female teacher and young male student locking eyes with the viewer in front of a blackboard containing a Black History alphabet. Joseph used the subjects as signals for the need for “new revolutionary vocabulary”. The artworks in this gallery are more direct in their presentation – with the artists not pulling any punches – using the material as a channel of expression.

Benny Andrews’ Did the Bear Sit Under The Tree?, 1969, stares at you with the shaking fists of a man who has had enough with the country whose liberties he thought he’d be able to thrive under. The rolled-up nature of the flag in this work was very telling as it could describe what you would find if you look behind the curtain of America, or possibly, a fed-up citizen rolling up his flag to discard it – because its meaning doesn’t apply to him anymore. Andrews along with Cliff Joseph created the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) in response to “Harlem on My Mind”, a 1969 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in which all the black artists in the neighborhood’s invitations to participate mysteriously got lost in the mail. I hope you can appreciate my sarcasm.

I loved the juxtaposition of the works by Faith Ringgold (The Flag is Bleeding, 1967) and Elizabeth Catlett (Black Unity, 1968). Ringgold’s work arranges three figures behind a blood-soaked flag. All are locked in arms with the figure of a black male obscured behind the stars. What makes this stand out, even more, is that the black male in the painting holds his hand on his chest – reminiscent of the pledge of allegiance – but is also clutching a knife. I would love to know what that’s all about. Catlett’s Black Unity, 1968, is a double-sided sculpture appearing as either a clutched black fist or a duo of faces depending on where the viewer is positioned. Made from mahogany, the bronze nature of the wood accentuates the message of “Black Power” – as it is polished to read as black skin. When I doubled back and looked again, it’s almost like the black male figure in Ringgold’s work is having a dialogue with the faces of Catlett’s sculpture. It’s as if they’re sharing an intimate secret, instructing folks to stand firm but always watch your back.

I was a little disappointed to see that American People Series #20: Die, 1967 by Ringgold was replaced in The Broad Museum curation, as I really enjoyed seeing it in the Tate Modern display. Why the change? Was the loan period was over from the MoMA? Who knows?

In the black community, “The Streets“ has been a term used to represent being excluded from the mainstream, forming an underground set of values. Many black artists sought visibility outside of the white cube by taking to muralism. As an addition to the display, the curators presented “Art on the Streets”, a slideshow of archived photography of these murals across America. Focusing on The Wall of Respect – a mural on Chicago’s South Side – the murals became a place for gathering, ultimately leading to a rise in muralism across black neighborhoods. Being a Los Angeles resident, places like Leimert Park and The Great Wall of Crenshaw come to mind as references to how the wave of black muralism inspired the optical tone of our neighborhoods.

Chicago was a key location in the Black Power movement and in some cases has been dubbed “The Heart of Black America”. Producing art movements like AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists), artists in the Midwest looked to add a new flavor and rhythm to contemporary painting. The group set out to paint positive vibrant images of black figures and penetrate the scene with an abundance of color. The works speak action into the gallery easily dominated by Wadsworth Jarrell’s depictions of Angela Davis in Revolutionary (Angela Davis), 1971 and Malcolm X in Black Prince, 1971. Both paintings burst with the images of the activists, surrounded by text that form to their features on canvas. Jarrell chose to use one of Malcolm X’s speeches at the bottom of the painting, giving power and emphasis to his words, while Davis’ image – pulled from a LIFE magazine photograph – was adequately decked out with a shoulder strap filled with wooden dowels (“bullets”), reflective of one of Jae Jarrell’s Revolutionary Suits – that was on display in the center of the room.

It was cool to also find the same admiration for Jarrell’s Revolutionary Suits in Jeff Donaldson’s Wives of Sango, 1971, which portrays three black women heavy militarized in formation, ready to take on anything that’s in their way. Donaldson presents the women as different ages, in different styles of clothing, and with different hairstyles – showing the varying appearances of the black woman – while concurrently alluding to their willingness to protect at all costs. If you’ve ever come across a black mother then you know this to be all too true. Carolyn Lawrence bursts with her colorful jazzy canvas work titled Black Children Keep Your Spirits Free, 1972, which resembles a poster from the psychedelic era, vibrant with color, and a slurred movement almost as if time is slowing down as your viewing.

As we enter “Black Light”- a gallery highlighting the work of black photographers – we come across an array of black and white works led by Roy DeCarva, showing his range in creating deep tonal photographs of life in New York City. Before seeing his work in the exhibition, I was under the impression that Gordon Parks – who is noticeably absent from the display – was the pioneer for the photographs of black life in America. I believe that while Gordon thrived in storytelling through documentary photography, Decarva set out to show blackness abstractly – focusing on the skin tone and features of the subject – creating drama through moments of calm. One of those moments came in the form of Shade Cord and Window, 1961, where a thin piece of string takes the form of a noose. Positioned close enough to where the window sill creates a bold shade of black, the string gently, quietly, and ferociously stands firm in the photo overlaying a building in the distance. This photo to me is quite moving. I believe Decarva spoke to the systematic racism in the inner city and how that ugly part of history seems to be inescapable.

Alongside the photography of Decarva, I was also introduced to the work of Beuford Smith whose 1968 photograph Man with Roses, 125 St. NYC, 1968, was another that stopped me in my tracks. Promoting black love, Smith seems to catch an older gentleman at random – possibly at a bus or train station as you noticed a woman walking with a bag in the background – waiting patiently with flowers for a loved one.

Also in the room was a vitrine featuring publications and photo books, under a curated selection of photographs by artists who worked concurrently, such as Herb Randall, Herb Robinson, Adger Cowans, Al Fennar, and Ming Smith. A nice bonus was seeing a digital copy of In Our Terribleness, 1970 by Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) and photographer Fundi (formerly Billy Abernathy). Fundi created the “Portraits of Life” in which Baraka responded with poetry. In his poem, Baraka explains his use of the word “Terribleness” as a way to uplift, a “new self-confident beauty”, enforcing the expression that “Black is Beautiful”. I would’ve loved to see the works of Howard Bingham in this section as well. His iconic black and white photographs of Muhammad Ali – a key Civil Rights figure – would have been in total sync with the tone of the exhibition as sports played a huge role in pushing the “Black Power” movement forward.

If there is one benefit to living in Los Angeles it’s that you get first-hand experience in Assemblage Art. From Noah Purifoy’s Outdoor Desert Art Museum to the sculpture of Betye Saar, the artists of the city have been the trailblazers of the movement, often incorporating elements of their reality to stage new experiences. Nails, steel, saxophones, and an old banjo case are just a few of the random items that you’ll encounter as you explore the oeuvre of the featured artists in the gallery. You’re welcomed immediately by Saar’s work Sambo’s Banjo, 1971-2 (On loan from California African American Museum (CAAM)) in which she uses the inside of a banjo case to stage a violent double lynching. In a plot twist, just above the victim, Saar – according to the documentation – left the tiny rifle visible for the character to free himself, ultimately placing his survival in his hands. This already sounds like a damn SAW movie. (Laughs.)

The room also features About Martin, 1975 by John Outterbridge who personally became a favorite of mine after seeing work of his at an exhibition at CAAM a while back. I again fell in love with this work as Outterbridge presents a tribute to Rev Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the form of a miniature closet resembling a military shadow box. A suit hangs in the space just under a picture of his widow Coretta Scott King, reminiscent of the wardrobe he wore in public. The suit sits on top of a black box with the names of the cities (Montgomery, Birmingham, Selma, Washington) where some of his most famous speeches were held.

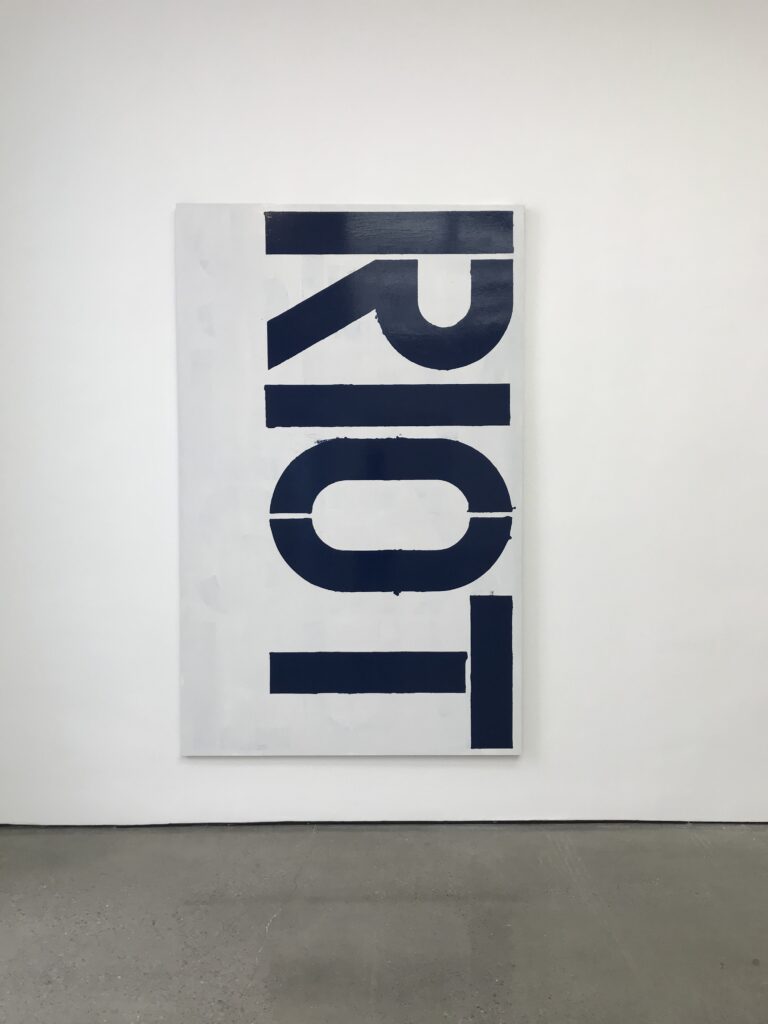

One new work by Noah Purifoy was added to the Los Angeles display, too much excitement of the local visitors. Watts Riot, 1966, contains debris from the 1965 Watts Rebellion to which Purifoy transformed into the work. The piece looks as if you’ll be able to still smell the charred material but good luck getting anywhere close enough to verify it. When I look at Watts Riot, 1966, I can see the influence of Purifoy on today’s contemporary artists like Mark Bradford – also from South Los Angeles – who employ the same anthropological process to art-making. With the museum featuring a few works by Bradford in its main galleries upstairs, it allows the show to draw connections and create a bridge for viewers to understand the artistic lineage. Sidenote: Mark Bradford’s Deep Blue, 2018 is a must-see.

Not to be outdone are the “Game of Thrones” style metal works by Melvin Edwards (Some Bright Morning, 1963, Afro-Phoenix #2, 1963 and Mamba, 1965) from his Lynch Fragment series. Commenting on social injustice, Edwards used the rough material of welded steel to present abstract visual commentary and possibly gaining acceptance into the Night’s Watch along the way. John T. Riddle’s Bird and Diz, Spirit versus Technology series, 1972 resemble Outterbridge’s work as collected materials are housed together to form a larger message. An homage to Charlie “Bird” Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, the work contains a saxophone and trumpet – which protrude beyond its casing – in what Riddle calls a “breaking out of the boxes,” referring to the musicians’ ability to transcend with their musical innovations. I would love to see how this work talks to Jean Michel Basquiat’s Horn Players, 1983 in the same space as it also speaks to the improvisational style of artistry that the musicians shared. Definitely worth a trip upstairs to compare.

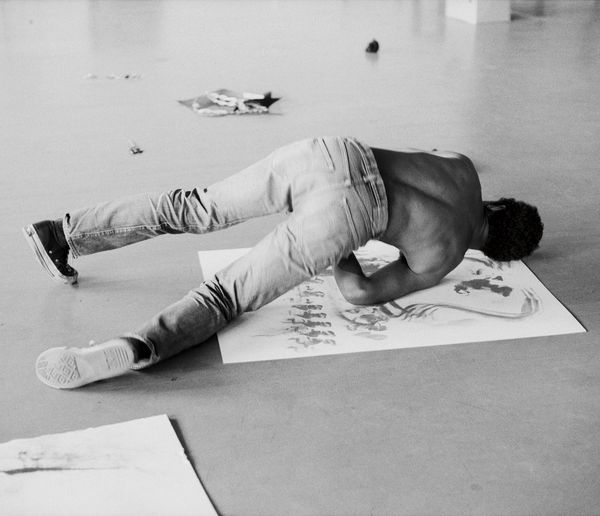

“Three Graphic Artists” dedicated to the 1971 exhibit of the same name at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) featured Charles White, – whose solo retrospective is currently on view at the institution until June 2019 – David Hammons, and Timothy Washington – who I’ve had the honor to meet through artist friends in the city. Under the mentorship provided by White, Hammons, and Washington were able to develop techniques that would help define their work for years to come. Hammons experimented with vegetable fat while Washington developed a new form of etching onto metal, visible in his work One Nation Under God, 1970.

The highlight of the show for me was David Hammons’ The Door (Admissions Office), 1969. In this work, Hammons’ famed body print technique – also on display in the remaining works by Hammons in the gallery (Black First, America Second 1970, Three Spades 1971, and Spade (Power of The Spade), 1969) – is displayed on an old wooden door reminiscent of the interior doors in a schoolhouse. On the glass that sits in the door under the words “Admissions Office” in vinyl, you see an oil-based imprint of hands, a face and part of a body giving off the strange appearance of “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot!”, a catchphrase derived from the 2014 murder of Eric Garner.

It was easy to see the references to the young black bodies sacrificed to the inequality of the American school system. It’s always icing on the proverbial cake when you continuously encounter work whose meaning is still just as clear today as it was during its inception. The display of this work brought up thoughts of nostalgia, as I was quickly reminded of the museums opening day in 2015 where the press was welcomed by picketing teachers making their voices heard about Eli Broad’s (Philanthropist and Founder of The Broad Museum) involvement in a plan to increase private education through charter schools. I wonder if any of the curators considered this? Or if they even remember that? Hmm. Carry On.

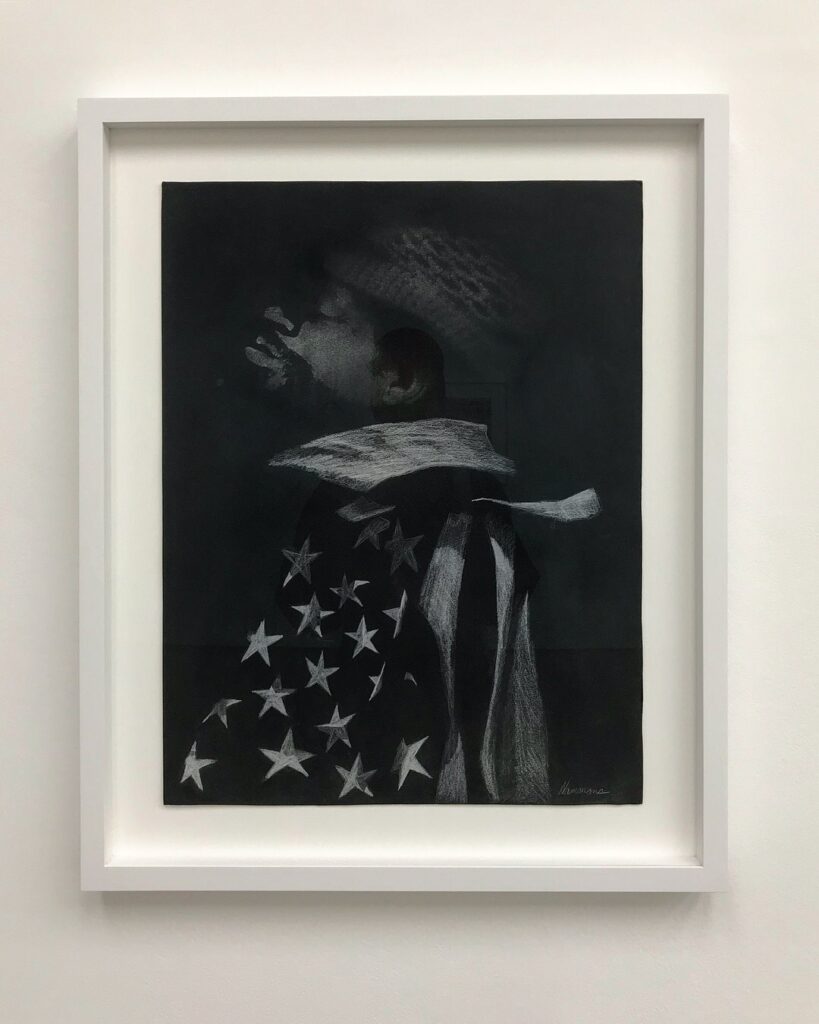

As you’re preparing to cross into the next gallery, you are forced to face Hammons’ powerful work Injustice Case, 1971. Again employing his body print technique, Hammons sought to bring awareness to the treatment of Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale during his trial – where he was bound and gagged after outbursts in the courtroom. A very harrowing image wrapped in the American flag, Hammons sought to “frame” the results of an oppressive structure, with the work appearing as an X-ray into the fabric of the American justice system.

I hate to write this, but the East Coast Abstraction gallery was my least favorite of the exhibition. I know, I know, it has powerhouses like Jack Whitten, Ed Clark, and William T. Williams but these works – while powerful on their own – just did not feel right together in this layout. These works are larger but lack the intensity of some of their smaller counterparts in the previous galleries – at least collectively. Speaking to the abstract nature of representation, these artists took to hard-edges and color staining as methods of creation, challenging the fact that blackness had to be rooted in figurative painting.

The gallery introduces its story with Jack Whitten’s Homage to Malcolm, 1970, an abstract tribute to the late Civil Rights leader Malcolm X. Executed on triangular canvas, the shape represents the pyramids of Egypt of which Malcolm visited on his pilgrimage to Mecca. With actions rooted in the Black Power Movement, Whitten took to his Afro-comb to move around the black paint in the center of the work – releasing hues of green, red and blue – and providing a ridged texture in the center.

Close by, you find Sam Gilliam’s April 4, 1969, a large stained canvas tribute to Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. marking the day of his assassination. This was one piece that presented itself to me as more of a representation of the evidence than a tribute. The dark reds and staining remind me more of the effort to save Dr. King’s life after he’d been shot. I see more of the blood-stained fabric of the first responders and friends who fought tirelessly to save his life. Maybe this is a tribute to them? Or maybe a reminder of what we lost as a community?

Trane, 1969, by William T. Williams provides the burst of color you’ve come to expect from abstraction with vibrant jagged lines that capture a multitude of colors finding their way through. Acting on the improvisation of Jazz – which he referred to as “Abstract Music” – Williams uses the hard-edged lines like a music visualizer, attempting to replicate the powerful sound from the performances of John Coltrane.

Peeking into abstract minimalism are the works by Virginia Jaramillo (Untitled, 1971), Daniel LaRue Johnson (D9 Flat 5th, 1969), and Tom Lloyd (Narokan, 1965) who was among the first to experiment with manipulating light as a form of art. It was really hard to experience the potential light show of Narokan, 1965 which was installed way too high to truly enjoy. This could’ve been done just a tad bit better in my opinion.

Before you crossover to the next gallery, you meet the egg-shaped canvas of Ed Clark with Yenom (#9), 1970. The work has a planetary feel reminiscent of gas giant Jupiter, with its landscape blurred – revealing only tidbits of the surface. It was interesting to read that this work (along with Virginia Jaramillo) was included in the racially integrated 1971 exhibition “The DeLuxe Show” in Houston, Texas. The show proved to be monumental as the artists descended on the Fifth Ward and provided the neighborhood with access to fine art and a foundation in which to look at black artists and modernism.

Cruising into the next gallery, you’re welcomed by the smooth and cool Barkley Hendricks who – with four large works – takes the lead in the space. The first of the Hendricks works you come across is Icon for My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved Any Black People – Bobby Seale), 1969. A portrait of the artist standing confidently against a heroic silver background, almost presenting himself as a packaged children’s toy with the “I’m all the hero you need!” moniker. With his arms crossed, he is seen sporting an afro and dark sunglasses – a tribute to the Black Panther Party leader Bobby Seale – and a Superman T-Shirt covering only up to the top of his pelvic area. Unlike his work Brilliantly Endowed (Self-Portrait), 1977, which sits across the gallery, Hendricks does a better job in this portrait of at least concealing his genitalia. (Laughs). The artist is posing naked with a white leather hat and sunglasses, wristbands, jewelry, socks, and sneakers with a very matter-of-fact demeanor. Hendricks’ exploration of his nude body stemmed from a review by the New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer – in which he referred to the artist as a “Brilliantly Endowed Painter”. Hendricks used his work (with that quote as fuel) to explore the black body as a subject while demonstrating his skill as a painter. I’ve often seen this work as a rebuttal to that of Robert Mapplethorpe and others, who were often criticized for their fascination with the black male body and the exploitation thereof.

Alice Neel presents a content Faith Ringgold seated in a bright red dress with floral print, led by dark blue strands of color that goes extremely well against the striped chair that she’s seated on. She has one hand clasping the other, as she stares directly at the viewer with a look of patience and security. Neel gives Ringgold what looks like two rosaries around her neck – possibly hinting at Ringgold’s commitment to her faith. Faith Ringgold, 1977, I believe focuses on the artist’s strength and commitment to her causes as an artist and woman, and Neel’s respect for her ambitious spirit, with the composition and position evocative of a presidential portrait.

Raymond Saunders’ portrait features the first African-American World Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson (Jack Johnson, 1971) as an armless dark green figure in a blazer, tie, and slacks mixed in a splash of color. Inside of the vibrancy, the artist scratches the signature of the champion vertically on the right of the subject, along with a date inscribed on the bottom left, maybe hinting at the reference photo that could have been the source for the work. I think of the color splash as the noise around him as he climbed the ranks in boxing to become the champion. With his mouth being the only visible feature, Saunders places a grin on Johnson as if to imply the artist “smiling through it all” as he moves forward through his success.

Emma Amos’ portrait pays tribute to an icon in her life with Eva the Babysitter, 1973. A yellow background sets the tone for the dedication, as she presents Eva seated comfortably in a red chair – smiling as she poses for the portrait. A child enters halfway into the frame – possibly Amos’ daughter unable to sit still during the process – insisting she is included. This addition of the daughter shows the loving relationship of Eva to the mother and child. I love how Amos adds the parquet floor with the red, white, and black carpet to break up the strong yellow in the painting, allowing for the reddish hues in the clothing of Eva and the seats to have more of a presence in the work.

I can remember the first time I saw Beauford Delaney’s Portrait of James Baldwin?, 1971. After reading the description I remember saying to myself, “How is there a question about the portrait if they were known friends?”. I’ll admit that there is something a bit off about the work, but it has all of Baldwin’s characteristics – the receding hairline and turtle neck were dead giveaways – and at the time the artist was going through a few mental health issues that could’ve made his memory of his friend’s facial features a bit skewed. The mustard color palette is a sharp contrast to the more colorful portraits by the artist of Baldwin. Like his 1945 painting (Portrait of James Baldwin, 1945) in which bright reds, bold blues and interchanging shadows of brown, yellow, and white accentuate the detail in the skin, giving a more impressionistic look. Although titled by Baldwin’s brother, Baldwin himself owned this painting and I’d like to think he wouldn’t keep a random look-alike painting (laughs).

The final two Barkley Hendricks works speak to his brilliance in using solid backgrounds of a specific color, while his subjects are overlaid with fabrics that mirror the tone of the backdrop. What’s Going On, 1974, always reminded me of a Motown singing group. Four of the five subjects in the painting are dressed in all white with hats to match, and the fifth one is a woman who is shown naked with her black skin as the beautiful contrast against the bold white background. Blood (Donald Formey), 1975, is a deep blood red painting of a man dressed in plaid, toting a tambourine staring firmly at the viewer. I’ve always wondered if the primary colors of these works were representative of something. Maybe the mood or vibe the artist got from the subject? Maybe it was the dominant colors in the clothing when he started his study sketches? Perhaps that’s research for another essay.

Improvisation and experimentation have always been key to the development of new forms of art-making and storytelling. Using materials from the unified experience of the black community, the artists in this section sought to expound on their practices by introducing new ways of presentation, allowing viewers to mentally participate in understanding the message. Alongside these materials are the stories that come with their use. Melvin Edwards’ powerful work Curtain (For William and Peter), 1969 – named after artists William T. Williams and Peter Bradley who were once his studio mates – is as haunting as it is provocative.

The work, very minimalist, employs barbed wire and chains to hint at the history of American slavery and incarceration. The barbed wire strands hang down from an overhead base connected by chain links. While at the bottom, each piece of wire is intertwined with the chains – calling attention to a prison chain gang or the terrible history of slavery in which groups of slaves were chained in unison to be sold. With prison reform a hot topic in current culture, this work almost feels contemporary as these same elements and materials are taking a larger role in our society with the privatization of the prison system.

Alvin Loving’s, Untitled #32, ca. 1975, and Joe Overstreet’s We Came from There to Get Here, 1970, are prime examples of how artists experimented with the installation and display of their work. Loving cut up his painted canvases only to sew them back up again into new realities, creating colorful collaged textiles. The works are very reminiscent of quilts that have been passed down through generations in the African-American community, with new additions as time goes on. Overstreet used the rope as a way of demonstrating the horror of lynching, but also the possibility of freedom with the rope also used a supports for the work. With its tent-like appearance, the work presents itself full of energetic color with a clever undertone hinting at black artists “setting up camp” in the art world – accentuating the speculation of a “black art” aesthetic.

Alma Thomas’ Mars Dust, 1972 – one of the paintings displayed in her 1972 Whitney Museum of Art Show – shows the artist’s fascination with space. With bright red brushstrokes overtop shades of blue (that try and peak through space in between), Thomas reimagines dust storms and landscapes as she sought to stimulate her fascination with space travel. A pioneer in abstract painting and a member of the famed Washington Color School, Thomas focused on movement, patterns, and consistency in abstract painting. Her work Watusi (Hard Edge), 1963, was selected by First Lady Michelle Obama for display in the White House. For an artist who was said to be overlooked, she was constantly on view in the West Wing during the Obama presidency.

The largest work in the gallery – Frank Bowling’s Texas Louise, 1971 – gives the viewer a feeling of approaching the peak of a mountain range to look at the sunset. Vibrant ranges of color blend with stenciled outlines of the continents, referring to the global mindset of identity. As you spend time with the work you can’t help but think of Bowling’s concept of the Map Paintings and how they relate to our current world. These works according to Bowling were to “celebrate a more fluid and open idea of identity and belonging to the world”, a contemporary concept talked about but rarely practiced.

Last but not least in the gallery is Jack Whitten’s Asa’s Palace, 1973, a large purplish canvas with islands of green paint that give the impression of vines in a wisteria tree. Using what Whitten called a “developer”, he created “rake-like” strokes, with the results imitating pulling the canvas fresh from a printer jam.

Entering the gallery dedicated to the work of Los Angeles-based artist Betye Saar is like stumbling into a secret antique store in rural Louisiana. The works are very ritualistic, with sculptures resembling altars and artifacts of ceremony that Saar uses almost as remedies, mentally inoculating the viewer through the context of each assembled object. Welcoming you into the gallery are Mti, 1973, and Spirit Catcher, 1977, two totem sculpted works with a myriad of materials. These two works are seminal as Mti, 1973, was featured in her first survey show “BETYE SAAR 1964-1973” at the Fine Arts Gallery at The California State University in Los Angeles and Spirit Catcher, 1977, is the result of a research trip to Haiti – in which she studied religious belief systems and practices. I have always been amazed at the practice of Betye Saar as it speaks not only her artistic imagination but the depth in her research as there is something new to find in every repeated encounter.

Above your head are Rainbow Mojo, 1972, and Eye, 1972, work made from cut and stitched leather topped with acrylic paint to mirror their respective subjects, hanging by clear string banner-like from the gallery ceiling. Nine Mojo Secrets, 1971 and Ten Mojo Secrets, 1972, face each other in the gallery, and to understand them both, I had to do my own research and it was very informative. I found out that a “mojo” is a charm that is lauded for its purported magic and ability to heal. It was also revealed that Saar’s zodiac sign is Leo, which explains the toy lion – a symbolic reflection of herself – in the work. The lion makes another appearance in Eshu (The Trickster), 1971, this time as a portrait made out of wood, leather, straw, and feathers. I like to think this work is the artist recognizing the strength associated with her zodiac sign. Bold and full of pride and power, the lion takes the form of an African mask or a stele made from contemporary materials.

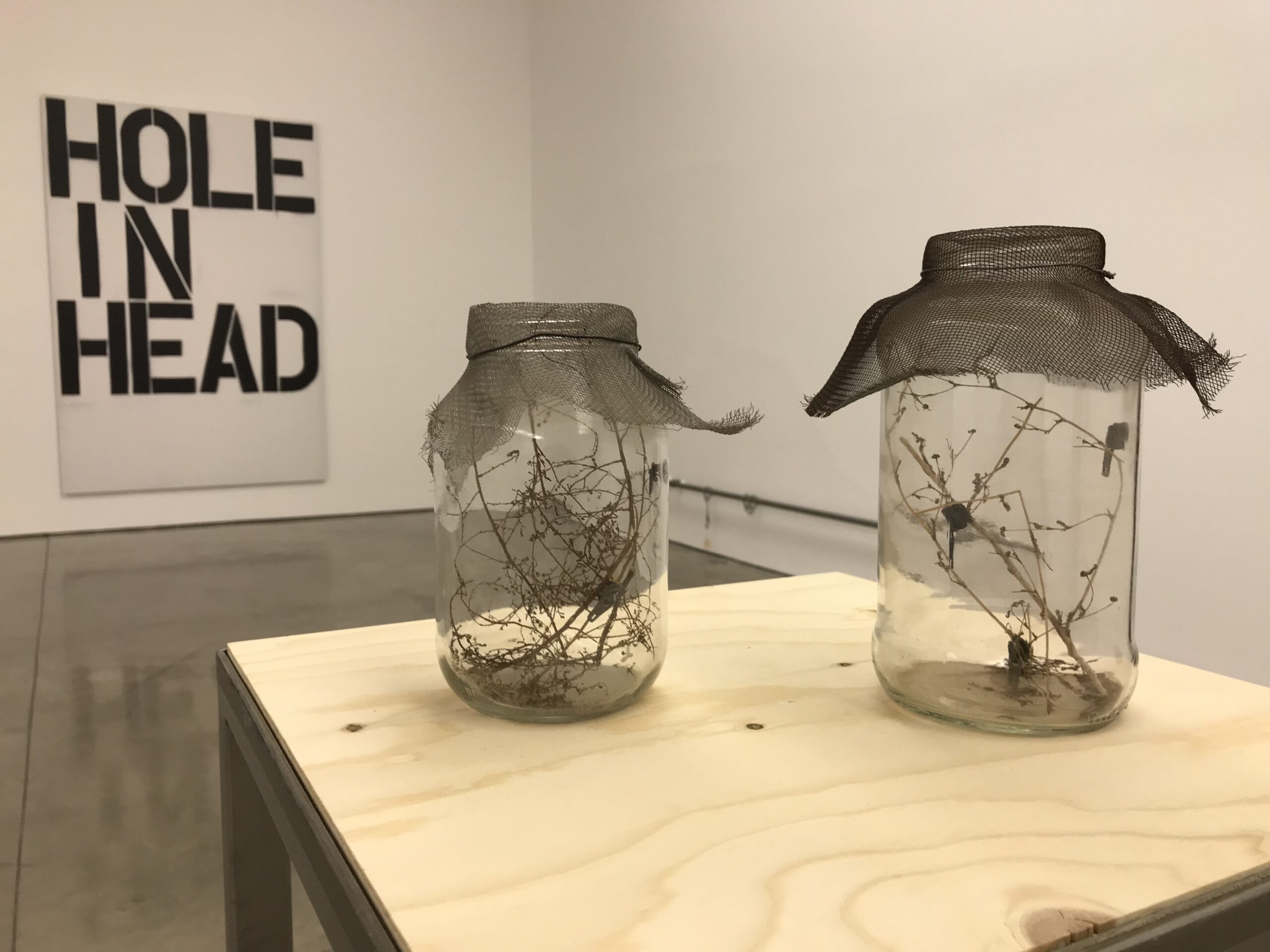

As you head up toward the finish line of the exhibition, you start to see light at the end of the proverbial tunnel. The exhibit starts to say its farewell as you can hear the crowd gathered in the lobby, awaiting their pilgrimage through the sea of visual black history. The final gallery is dedicated to the work and legacy of Just Above Midtown, – better known as “JAM”- a gallery program created by Linda Goode Bryant, focusing on exhibiting the work of African American artists. Situated in the heart of New York’s commercial art world, Bryant created a marketplace for the work of artists of color to be “seen and work to be sold”, becoming a center of black art exhibition, and a space for avant-garde ambition.

In the vitrine placed at the center of the gallery were Items from the JAM archive, including installation photographs, exhibition posters, catalogs, and publications as well as performance documentation that captured the essence of the gallery’s programming throughout its duration. It is amazing to see the amount of pride and also growth that the space produced during its history, lasting from 1974–1986.

The artists featured in the gallery were instrumental to the rise and success of JAM. By creating work that allowed for discussion, immediately provided insight into an artist’s vision. Artists such as David Hammons and Senga Nengudi used activation as a form of interaction, creating works that were lauded and also heavily debated. JAM was able to use interaction as its calling card, staging large-scale projects inclusive of the community like Lorraine O’Grady Art Is…, 1983 at the 1983 Harlem African American Day Parade.

Her forty-part photography series featured selected portraits of Harlem residents along with local storefronts and building facades that represented the fabric of the community. As the story goes, Grady entered a float in the parade which displayed a large gold picture frame. She also hired fifteen dancers to survey and interact with the parade crowds with smaller gold frames, extending the experience. In essence, to be inclusive, Grady used the public performance as an opportunity to finally “include” black people in contemporary art as many of the onlookers and participants jumped at the chance to take part.

Senga Nengudi creates works based on performance using nylon tights among other objects such as sand and rubber. I laugh when I think of my first encounter with her work in London. I initially felt cheated as if someone was playing a trick on me. For me, that was the final straw in this new contemporary art scene. “Tights with sand? How fucking desperate are we?” I thought, not knowing how uneducated I was to the power the artist had in her performance. It wasn’t until I came across the Tate Modern’s video series “TateShots” and viewed an interview with Linda Goode Bryant and Senga Nengudi did I truly comprehend the level of artistic genius she exhibited.

Her work Internal II, 1977, 2015, reminds me of a spider’s web providing support to the walls of the gallery. As I learned more about the work, I understood that it spoke to the strength of the female body and it then it made sense. Senga mentions in the “TateShots” video how the nylon is at “wit’s end” from being stretched to the point of anxiety. I immediately felt a connection to the work and how it represented my mother, a strong single woman who stretched everything she had as far as she could to see me and my brother succeed. Even if it meant she would herself be stressed and challenged beyond her greatest capabilities. As Nengudi relates it to black females, she comments on the female body being reflected abstractly as being “used” and I contemplated the way we view women and beauty standards in society. I started to think of the women who struggle to return to their normalcy after childbirth and how tough that can be. I believe this was a great way to deliver the message as you could see the strength in the fragility, a perfect reference to the female body.

David Hammons’ Bag Lady in Flight, 1975, reconstructed in 1990, leads off the display of his works shown in previous exhibits at JAM. I swear when I look at this work I hear Erykah Badu’s song, “Bag Lady”. Made from shopping bags, grease, and human hair, Hammons looks to these materials and the results of the incorporation as a dedication to the positivity they hold in the black community. I see this work as a tribute to the spending power of the black woman. With the hair and grease being primary materials in the work, I think of companies like Bronner Brothers and how they have built a billion-dollar industry with hair care products all through the spending of black women. Funny enough being from Philadelphia, a brown greasy bag has always made me smile because inside of that bag usually awaited a cheesesteak which could explain my immense hunger after the exhibition. (laughs)

Also included was Untitled, c.1980’s, a wall sculpture made from pork ribs, tire inner tubes, and costume jewelry that I still can’t grasp the meaning of. I’d like to think it represented part of his upbringing and the materials and objects that were part of his everyday life. Just as in Bag Lady In Flight, 1975, Hammons uses the items to spark a form of nostalgia, tying seemingly different items together. Maybe this was a dedication to summer cookouts and neighborhood bike riding?

One of the absolute coolest works in the exhibition is Dawoud Bey’s A Boy in front of the Loews 125th Street Movie Theater, 1976, printed by 1979, showing an adolescent boy decked out in the latest fashionable tracksuit, a stylin’ pair of shades, holding what appears to be a juice carton posing on a wooden barricade in front of the theatre. The most notable thing in the photos to me was the kid’s bright white sneakers, as the beautiful contrast in the photo makes them seem to glow. This effect is also replicated in A Woman at 7th Avenue & 138th Street 1976/7, printed by 1979, where the subject’s shoes and purse reveal a similar radiance.

Howardena Pindell’s Untitled, 1978, and Randy Williams’s, Color in Art, 1976, round out the gallery displaying new abstract assemblage practices within. In Pindell’s Untitled, 1978, she uses hole-punched dots to create a texture similar to braille on top of a re-sewn canvas. The work merges the senses as each looks deeper it seems as if you can feel the texture across your fingertips. Prompting you to reach out only to be reminded to “please stay a foot behind the line” by the gallery attendant. In Color in Art, 1976, Williams uses wooden window shutters as the structure for the work accompanied by rope and a book screwed down to the wooden frame with a plexiglass plate. Williams’ work deals with the parallel themes of inclusion/exclusion, a topic he feels still needs some addressing as he continues to develop his practice while working as a college professor.

As I exited the final gallery, I ran into Self, 1978, by Martin Puryear (Puryear will represent the U.S. in the 2019 Venice Biennale) which I must’ve completely missed walking up to the exhibit entrance. In the Tate Modern curation of the show, the work was featured in the Improvisation and Experimentation gallery but somehow made its way outside the exhibition in LA. Possibly to highlight his Biennale accomplishments which I certainly am not mad at. The work is made of cedar and mahogany stained black, sticking upwards off the plinth resembling the fin of a shark on the hunt. The work as the artist explains is a representation of self as a secret entity that appears heavy and strong but in all actuality is quite hollow. If that ain’t a jab at humanity I dunno what is. But Puryear is careful in his interpretations often leaving it up to the viewer. He stated, “I value the referential quality of art, the fact that a work can allude to things or states of being without in any way representing them.”, creating his form of symbolism as a vehicle for characterization.

So what’s is the next step after Soul of a Nation? Is this the beginning of the retrospective for black art movements? Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983 was a great insight into the artistic movements that existed during the Black Power era and serves as a visual history. Are era-based retrospectives the best way to understand the African-American contribution to the global art world? As I write this essay I think of what I’ve learned just by observation. The research of artworks allowed me to understand the artists’ backgrounds, their materials, and how their use of them helped to change and develop the practice of art-making. It uncovered artistic movements that mirror those of contemporary art today, adding credence to the “history always repeats itself” saying. It also was a strong reminder as we look in that same mirror, that many of the reasons for collectives like the Spiral Group and Just Above Midtown still exist today, with black artists and professionals combating issues of inclusion in museums and blue-chip galleries in new ways.

This retrospective has activated the city with showings of black artists, as local galleries and museums are presenting complementary shows adding appreciation to the contributions of black artists to the fine art canon. I wonder how or if this exhibition will improve the primary and secondary markets of the participating artists? Will artists like Betye Saar, Jae Jarrell, and Alma Thomas start to enjoy the same market success as Njideka Akunyili Crosby now that this show has made its mark? How long will these works remain with their current collectors? It will be very interesting to see what the future holds for the careers of these artists, but for now, we can all enjoy and bask at the moment for however long it lasts.

Soul of A Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983 is on view at The Broad Museum, 221 S. Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012. Through Sep. 1st, 2019, https://www.thebroad.org.